Introduction

Over the last few years, we have seen more enterprises open to adopting public cloud and migrating at least some of their data sets. Understanding how data can be protected in the cloud is a common question from teams less familiar with this technology. In this two-part blog post, we will first build an understanding of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) then look at some aspects of protecting this sensitive data in the cloud, especially from a Serverless perspective.

Types Of Data

While we will focus on PII data, many of the ideas presented here can apply to other types of sensitive data. Knowing the types of data your organisation has, classifying them, setting a sensitivity level and having policies to address requirements and cloud approval are essential first steps in moving any data to the cloud.

While data classifications may vary across countries and generations, the Centre for Internet Security uses ‘sensitive’, ‘business confidential’, and ‘public’ for high, medium, and low sensitivity levels. Laws protect high-sensitivity data, medium-sensitivity data is intended for internal use, while low-sensitivity data is used to denote publicly accessible information.

With internal alignment on types of data and levels of sensitivity, an organisation can classify each data set within the organisation. Then, a policy can be established for each type-level combination that sets out requirements for moving this data to the cloud.

Application teams can then more easily find out if their application data can be stored in the cloud and determine the specific service configuration requirements to do so in a compliant way.

Personally Identifiable Information (PII) Data – A Definition

As the name suggests, PII is any data that can be used to identify a specific person. The data may be used by itself or combined with other data sets in order to determine an individual’s identity. Information from a driver’s license, banking details, government ID number, and medical records are considered sensitive PII. Meanwhile, publicly available data such as a person’s race, gender, or date of birth are considered non-sensitive PII.

Note that the definition of PII varies from one country to another. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) defines personal data as “any information that relates to an individual who can be directly or indirectly identified”. The definition covers names, email addresses, location information, ethnicity, gender, biometric data, religious beliefs, IP address, political opinions and even pseudonyms or usernames that are easily linked to a person.

In Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), PII includes “any (digital) information that can be used to decipher the owner’s identity.” In this definition, personal email and mailing addresses, contact numbers, and credit card information are examples of PII. Business email addresses are actually exempt from PII in PDPA – one of the significant differences with GDPR. Read more about some of the differences between PDPA and GDPR in our earlier article here.

The Importance of PII Data

PII is distinct from other types of data in that it can be used to pinpoint a person’s identity. As mentioned, there are two types of PII: sensitive and non-sensitive. Sensitive PII is the type of information that, when leaked, could lead to an individual’s harm. Thus, sensitive PII needs to be especially protected, and fines for loss of this data may be considerably higher.

More than preserving company secrets or other business-related communications, significant fines and possible reputational harm resulting from a breach and loss of personal data are key motivators for organisations to handle personal data securely. As a case in point, Google was not spared from GDPR in 2018. France’s Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL, National Commission on Informatics and Liberty) issued Google with a fifty million Euro fine for giving vague and generic descriptions of important details such as their legal basis for data processing and their data retention period, among other violations. The CNIL publicised the sky-high fine to emphasise the severity of Google’s infringements, and serve as warning to others.

Though many users still patronise Google, some have explored options like DuckDuckGo, which promises never to track users nor store personal information. Interestingly, DuckDuckGo’s popularity surges whenever major data breaches occur, such as Edward Snowden’s 2013 exposé, and the Cambridge Analytica scandal. This shows that many citizens, especially privacy-oriented ones, will choose companies that handle their data properly and abandon companies that are seen to be careless, vague or manipulative. As such, it pays to be genuine, proficient and vocal about your organisation’s approach to privacy.

Key Concepts Definition

Before we delve more intimately into the common requirements of privacy regulations and how we can address them, let’s first define a couple of key concepts.

Shared Responsibility

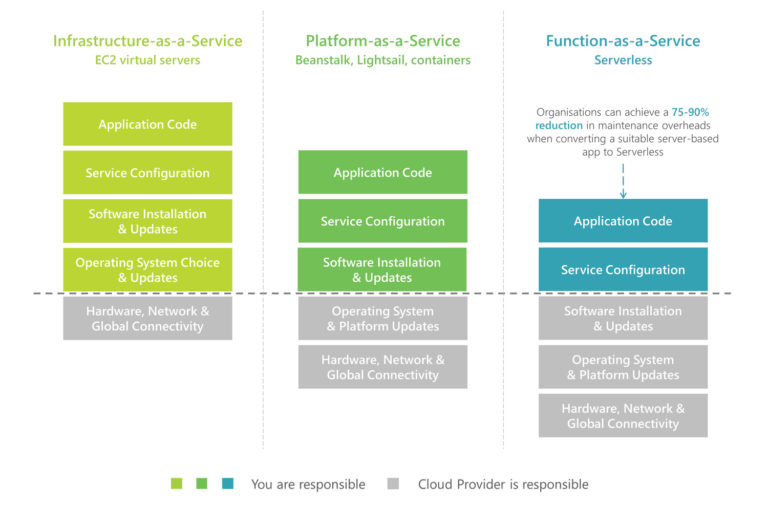

Shared responsibility is a common concept adopted by all cloud service providers. It is an approach to cloud security that expects both parties – the cloud provider and the account owner – to be responsible together for the security of the cloud account and the data in it. For example, the cloud provider is responsible for physical access to their data centres, while the account owner is responsible for access permissions to the cloud account itself as well as to any databases in the account. These responsibilities are clearly defined, and together are critical to the security of the cloud environment.

On a high level, the more abstracted or managed a cloud service is, the more responsibility sits with the cloud provider. With servers in the cloud, the provider’s responsibility encompasses physical access and most of the network. The organisation is responsible for firewall configuration, access permissions and everything in the virtual servers, such as patching of operating systems and software to ensure their security.

With Serverless, the organisation is only responsible for the microservice code, specific security configuration, and access permissions. The increased responsibility that sits with the cloud provider significantly reduces the burden on the organisation. For example, the cloud provider is responsible for achieving certification against many security compliance programs for its fully managed services. Many services include difficult to achieve security compliance certifications such as HIPAA and PCI. More details on this for individual AWS services can be found here.

The Principle of Least Privilege

Privilege means access or permission; it sets what a given user or service has access to within an IT environment. This principle is about providing an entity – a user or a service – with only the bare minimum permissions that they need, ideally at that point in time, or at least a given time frame.

Common Requirements of Privacy Regulation

A few common privacy regulation expectations can be at least partially addressed in the cloud with Serverless. All of these tend to figure to some degree in multiple privacy regulation laws around the world. Some are more prescriptive in how they want these addressed; others only require that these are addressed in some fashion. In this blog post, we will be focusing on the following three common requirements: tracking, protecting, and retaining data.

- Tracking Access

The requirement for accountability and ability to demonstrate compliance can be considered a cornerstone of GDPR, PDPA and other privacy regulations. Access to data is arguably one of the most significant risks to data. Logging exactly who accesses data, when they access it, and via which channel they accessed the data will provide an organisation with the means to demonstrate compliance in the cloud. Being able to react to suspicious access events in a timely fashion will similarly show competence and help minimise the impact of a potential breach in progress. - Protecting Data

Data protection must be integrated “by design and by default” by organisations that fall under the jurisdiction of the GDPR, even with old products or services. Meanwhile, the PDPA states that “the organisation must protect personal data and are responsible for making reasonable security arrangements”. Principles of data protection are outlined in Article 5, including “protection against unauthorised or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage, using appropriate technical or organisational measures”. - Retaining Data

Data should not be retained longer than necessary under the GDPR as well as the PDPA. Data erasure or the “right to be forgotten” is also upheld by the GDPR. This right means that data subjects may request the erasure of their data when, for example, data is unlawfully processed or even if they simply want to withdraw consent.

Conclusion

Now that we have developed a common understanding of PII, its importance and the requirements often applied to it through privacy regulations, proceed to our next blog in this series to read on how Serverless technologies can be leveraged to ease the burden of meeting these regulatory requirements and protecting your organisation from any breach or leak.

Thomas is a Lead Consultant at Sourced with over 18 years of experience in delivering digital products. He gained a passion for evangelising Serverless architecture through his enthusiasm for cloud and entry into the AWS Ambassador programme.